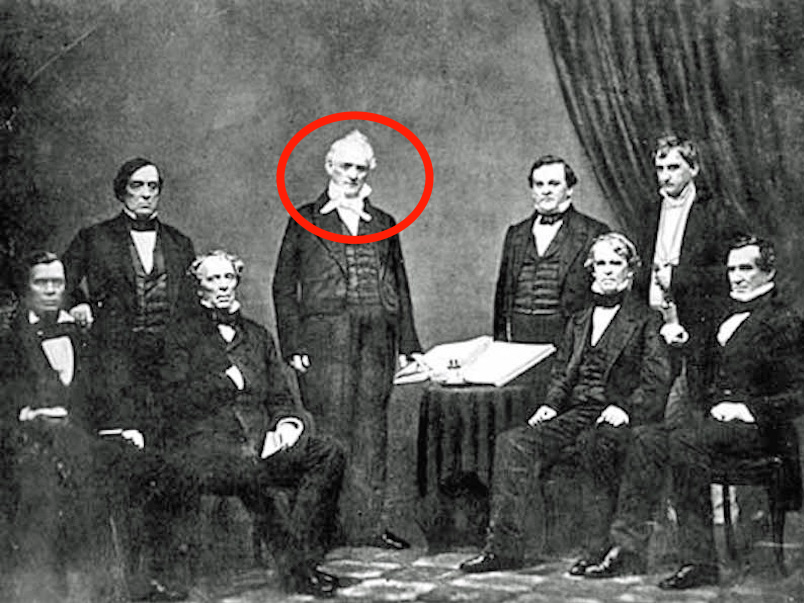

Harry Truman (pictured) was a pretty dedicated Freemason.Wikimedia Commons

Harry Truman (pictured) was a pretty dedicated Freemason.Wikimedia Commons

Secret societies always get the ominous treatment in fiction.

Are there any movies with remotely benevolent secret orders? Most fictional secret societies are usually more bogged down with dressing in outdated robes, chanting ominously, doing sacrifices, or hatching nefarious global plots.

So, to the paranoid mind, it probably sounds somewhat startling that 20 out of 45 US presidents have been affiliated with some kind of secret group. Just keep in mind that many of these societies function a bit like social clubs, charitable organizations, and business networks. In many cases, beneath the secret handshakes and mysterious rituals, they're kind of like adult frats (or actual frats, in the case of the college groups on this list).

Here are the presidents who have belonged to a secret society at some point:

George Washington, Freemasons

That's right. The first president of the US also happened to be rather involved in a secret society.

That's because George Washington was also the country's first ever Masonic president.

In Ron Chernow's "Washington: A Life," he notes that the future president may have been attracted to the Masonic Order's adherence to Enlightenment ideals.

Washington joined the Order of the Freemasons early in his life, entering Fredericksburg Lodge No. 4 at the age of 20, according to Mount Vernon's official website. Washington had lost his older brother Lawrence to tuberculosis only a few months earlier, effectively becoming head of the household.

Washington stayed in touch with his Masonic brothers for the rest of his life.

Masonic influences came into play at Washington's first inauguration. During the ceremony, he swore his oath on a Bible from St. John's Masonic Lodge No. 1 in New York (the book, as Mental Floss reports, was randomly opened to Genesis 49:13: "Zebulun shall dwell at the haven of the sea; and he shall be for an haven of ships; and his border shall be to Zidon").

The first president's Masonic ties followed him his entire life — and beyond. There's even a George Washington Masonic National Memorial, which was dedicated in 1932 and finally completed in 1970.

Thomas Jefferson, F. H. C. Society

Thomas Jefferson may have been a member of the F.H.C. Society at the College of William and Mary, but that doesn't mean he was impressed by the group.

In one 1819 letter, the third US president reflected on his experience in the secret society: "... there existed a society called the F. H. C. society, confined to the number of six students only, of which I was a member, but it had no useful object. Nor do I know whether it now exists."

Ouch.

The initials F.H.C. stood for "Fraternitas, Humanitas, et Cognitio" — Latin for "brotherhood, humanity, and knowledge." However the group became known as the Flat Hat Club, probably a reference to the mortarboards all students wore in those days.

Members identified themselves with a secret handshake, along with a silver badge inscribed with the words "stabilitas et fides" (stability and faith, which is now the motto of William and Mary's campus newspaper). Perks included exclusive parties in the upper rooms of the local taverns, according to "Mr. Jefferson's Women. "

The group pretty much died out when the Revolutionary War interrupted classes. However, the name lived on with William and Mary's student newspaper and the secret society itself re-surged in 1972, under the name the Flat Hat Club.

James Monroe, Freemasons

Mason website The Masonic Trowel lists Monroe as entering the Williamsburg Lodge No. 6 in 1776. At that time he was a 17-year-old student at the College of William and Mary, and heavily involved in anti-Crown activities on campus.

He's recorded as paying dues to the lodge from 1776 to 1780, according to "A Comprehensive Catalog of the Correspondence and Papers of James Monroe: Volume I."

Over the course of those four years, the future fifth president would drop out of college to fight in the Revolution, nearly die after getting shot during the Battle of Trenton, and then return to William and Mary to study law.

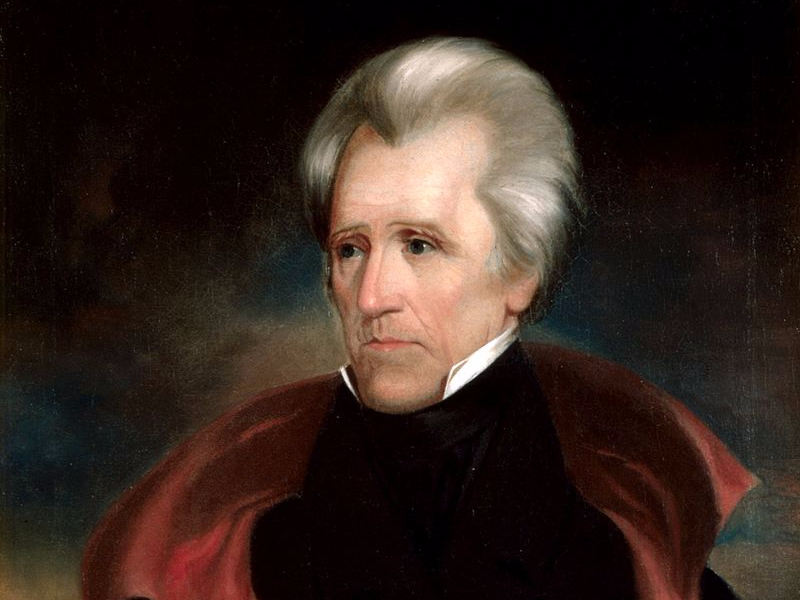

Andrew Jackson, Freemasons

Jackson's status as a Mason actually became a major political issue during his presidency.

That's because the first ever third party in US politics formed as part of a backlash against the Freemasons.

As Slate reported, the seeds for the Anti-Masonic Party were first sown in 1826, when Masons were implicated in the (still unsolved) kidnapping of a New York man who threatened to reveal their secret rites. The political party opposed what it perceived as a sinister, elitist, and anti-democratic secret society.

The Anti-Masonic Party found a natural foe in Jackson, who was not only a Mason, but a high-ranked one. Jackson served as the grand master of the grand lodge of Tennessee from 1822 to 1824.

James K. Polk, Freemasons

According to the "Proceedings of the Grand Lodge of Kentucky," the 11th president "... was initiated in Columbia Lodge No. 31, Columbia, Tennessee, June 5, passed August 7, and raised September 4, 1820."

He was 25 at the time, and has just been licensed to practice law.

James Buchanan, Freemasons

According to "The Complete Idiot's Guide to Freemasonry," Buchanan was raised to Lodge No. 43 in Lancaster Pennsylvania.

Buchanan later went on to become one of the consistently worst-ranked presidents in US history.

Andrew Johnson, Freemasons

In her biography on Johnson, historian Annette Gordon-Reed says that the former president remained a "proud Mason" throughout his life and that "the local Masonic temple played a great role in the funeral proceedings."

Ulysses S. Grant, Independent Order of Odd Fellows

18th US President and famed Union general Ulysses S. Grant was an Odd Fellow.

That is, he belonged to a society known as the Independent Order of Odd Fellows.

This fraternal order has its roots in early modern Europe and was an offshoot off of England's Odd Fellows. The American version of the organization was officially founded in 1819 in Baltimore. The order focused on charitable causes and eventually admitted both men and women as members.

According to "The General’s Wife: The Life of Mrs. Ulysses S. Grant," Grant, who struggled with drinking at times, joined the Order after his wife became pregnant with their second child.

"The Papers of U.S. Grant" feature an invitation from the Order asking then-President Grant to attend its 50th anniversary celebration in Philadelphia in 1869.

James Garfield, Freemasons

Garfield only served a few months of his presidency before being cut down by an assassin's bullet. He had a lengthier tenure in the Freemasons.

According to the "Proceedings of the Grand Lodge of Kentucky," he "... was initiated in Magnolia Lodge No. 20, Columbus, Ohio, November 19, passed December 3, 1861, and raised December 22, 1864. He also received the Capitular and Templar degrees, and those of the Lodge of Perfection in the Scottish Rite."

Rutherford Hayes, Independent Order of Odd Fellows

A list of Hayes' speeches shows that the 19th president spoke to gatherings of Odd Fellows five times from 1850 to 1887.

In his 1887 speech in Fremont, Ohio, where he ushered in the appointment of new Odd Fellow officers, Hayes discussed his own feelings about the order and other societies like it:

"The beneficial societies, commonly known as secret societies (in fact, they are secret chiefly in name, and secret only to guard against imposture) these societies gather under the same friendly roof in close intimacy persons differing widely in occupation, politics, religion, and conditions of life and fuse them easily and naturally into complete harmony and cordial friendship."

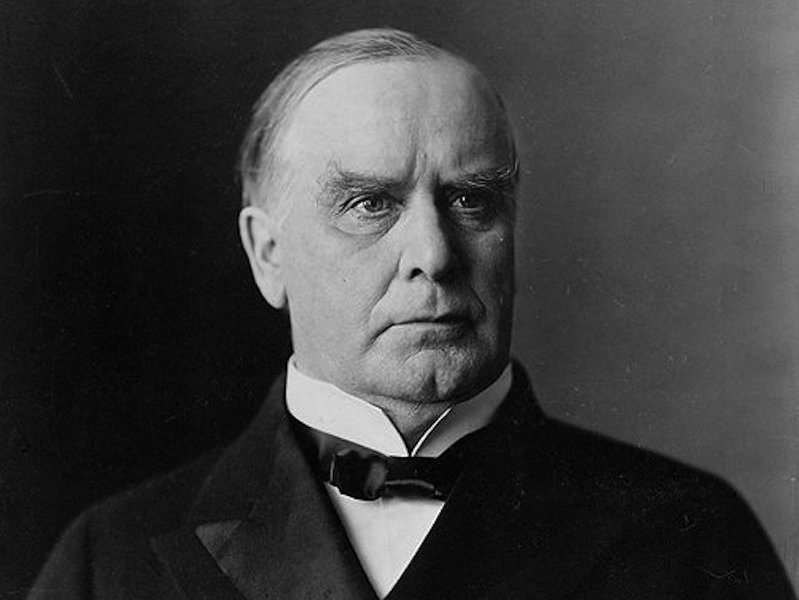

William McKinley, Freemasons, Independent Order of Odd Fellows

McKinley succeeded Garfield as both the next Masonic president and the next president to be assassinated.

Roadside America features a post documenting the site where McKinley was first initiated as a Mason, while fighting for the Union during the Civil War.

His Masonic legacy lives on today, as the lodge he once belonged to is now named after him.

The Odd Fellows also claim McKinley as one of their own.

Theodore Roosevelt, Freemasons, Concatenated Order of Hoo-Hoo

The Theodore Roosevelt Center has digitized many of the 26th president's letters — some of which reference his Masonic activities.

President Roosevelt addressed the Grand Lodge of Pennsylvania in 1902 on the anniversary of Washington's initiation. In his speech, he reflected on some of his own reasons for joining the Freemasons:

"One of the things that attracted me so greatly to Masonry, that I hailed the chance of becoming a mason, was that it really did act up to what we, as a government and as a people, are pledged to — of treating each man on his merits as a man. When Brother George Washington went into a lodge of the fraternity, he went into the one place in the United States where he stood below or above his fellows according to their official position in the lodge. He went into the place where the idea of our government was realized as far as it is humanly possible for mankind to realize a lofty idea."

However, Roosevelt also ran into occasional snags with the society. In his letters, he chastised one alleged Mason for attempting to use his position in the society for political advantage (which is against the rules of Freemasonry), and complained about another situation in a letter to a friend, writing that one foe was "... endeavoring to use Masonry to my political disadvantage."

After his presidency, Roosevelt wrote about traveling the world and visiting Masonic lodges in Nairobi and the Azores.

Roosevelt wasn't just a Mason, however. He also belonged to the comparatively obscure and ridiculously named International Concatenated Order of Hoo-Hoo. What the heck is that? Well, as Forest History Society blogger Amanda T. Ross writes, "The Hoo-Hoos resemble less an exclusive secret society and more a business fraternity." It was a fraternal organization for men in the lumber industry, and boasted TR as one of its most famous members, due to his conservation work.

William Taft, Skull and Bones, Freemasons

The 27th president went by "Old Bill" during his Yale days but later earned the nickname "Big Lub."

Taft also received the honorary title of "magog," meaning he had the most sexual experience while in the secret club, according to Alexandra Robbins at The Atlantic.

Young Taft probably found entrance into the club rather easily. His father, former Attorney General Alphonso Taft, cofounded Skull and Bones as a Yale student in 1832.

Many years after graduation, Taft ended up joining yet another secret society when he became a Mason in 1909, about a month before his inauguration.

The 1912 record book "Proceedings of the Grand Lodge of Free and Accepted Masons of the State of New York" mentions that Taft "in his high and influential of President of the greatest and mightiest Republic of the world" was applying Masonic principals in his attempts to handle world affairs.

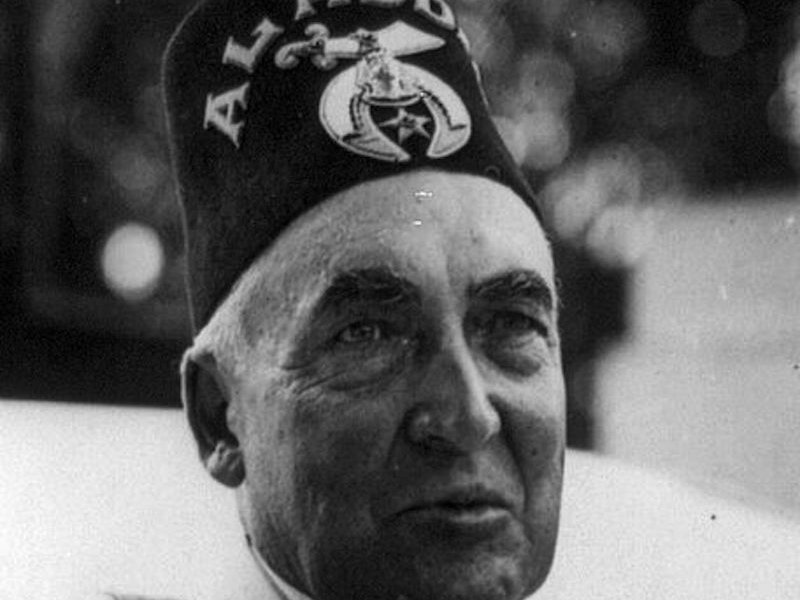

Warren Harding, Freemasons, Independent Order of Odd Fellows, Concatenated Order of Hoo-Hoo

Harding was first initiated as an "entered apprentice" with the Masons on June 28, 1901 in Marion Lodge No. 70 in Marion, Ohio.

However, the 29th president of the US wasn't officially raised to the level of Master Mason until 19 years later.

The timing of his acceptance just happened to coincide with Harding's presidential campaign — and subsequent victory.

A paper by Mason and researcher John R. Tester details Harding's long-thwarted quest to rise within the secret fraternal society. Tester theorizes that the reasons for Harding's delayed promotion may have been due to political prejudices or rumors about his black ancestry (most Masonic lodges refused to admit African Americans for much of US history).

Harding seemed to have an easier time as a member of the Independent Order of Odd Fellows. As the Seward City News reported, when the president visited Seward, Alaska, he was received in the town's Odd Fellows Hall. A 1921 edition of the Chicago Lumberman also lists Harding as being a member of the Concatenated Order of Hoo-Hoo. So, while historians rank Harding has a pretty subpar president, he was a triple threat when it came to secret societies.

Franklin Delano Roosevelt, Freemasons, Independent Order of Odd Fellows

Roosevelt was first initiated as a Mason in 1911, and later became a grand master in 1934.

The Franklin D. Roosevelt Library and Museum's official blog features several historic materials pertaining to the three-term president's participation in the society.

One excerpt from a 1935 press conference features Roosevelt's account of a Mason-related prank he pulled on then-Securities and Exchange Commission Chairman Joseph Kennedy (the father of future president John Kennedy).

The day after the press conference, Roosevelt conducted a ceremony raising his two sons at the Architect Lodge. Afterwards, the president gave a speech praising the society: "To me, the ceremonies of Freemasonry in this state of ours, especially these later ones that I have taken part in, always make me wish that more Americans, in every part of our land, could become connected with our fraternity."

But the Masonic Order wasn't the only secret club that FDR was a member of. Like his predecessor Grant, he also belonged to the Independent Order of Odd Fellows, as Houstonia Magazine reported.

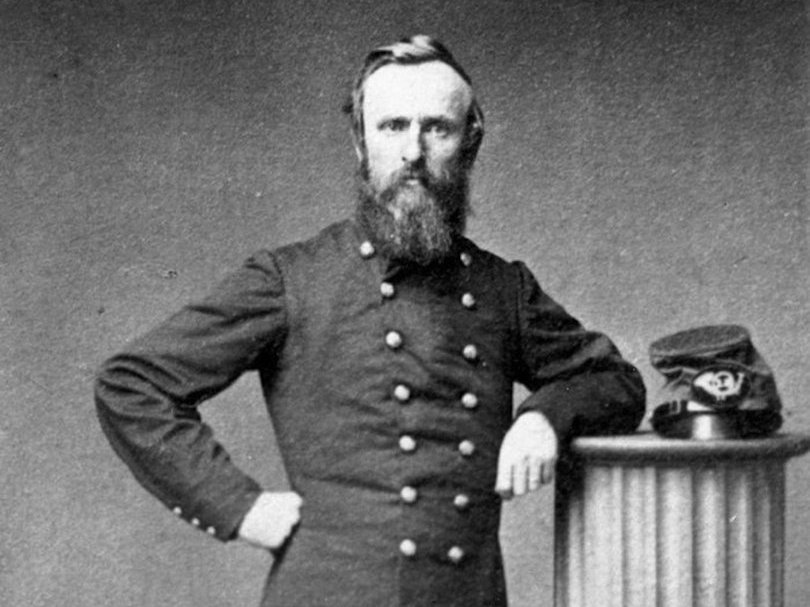

Harry Truman, Freemasons, Independent Order of Odd Fellows

Truman was very involved with the Freemasons, all the way back from his time in Belton, Missouri. In fact, the 33rd president helped found a Masonic Lodge there in 1911 and was elected its first master, according to the Truman Library.

The young Missourian was immediately hooked on Freemasonry. The Truman Library also cites some of Truman's letters to his future wife Bess Wallace, during which he confessed to having "the big head terribly" and warned her that he'd forever "... be bragging about having performed that ceremony."

Apparently, Truman's lodge hall burned down while he was serving in WWI, but he continued to rise within the Freemasons throughout the 1920s.

The Truman Library cited one observer's assessment of Truman's leadership abilities in the society: "… He did a good job in the lodge work. Excellent. He was an excellent director. If things weren't going right along smoothly, Harry would come in and get them to going. He was a good lodge man."

He eventually became a grand master mason, but ended his role in a "blaze of glory" the next year, while still a US senator.

A few years later, during his presidency, he remained a committed Mason. The New York Times reported that Truman's "only jewelry was a double-band gold Masonic ring on the little finger of his left hand." The Truman Library also reports that in 1945 Truman became the only president to received the 33rd degree of the Supreme Council of the Scottish Rite. He also is said to have been a member of the Odd Fellows, although this isn't nearly as documented as his adherence to the Masonic Order.

In "Harry S. Truman: His Life and Times," Brian Burnes quotes Truman as writing: "Freemasonry is a system of morals which makes it easier to live with your fellow man, whether he understands it or not."

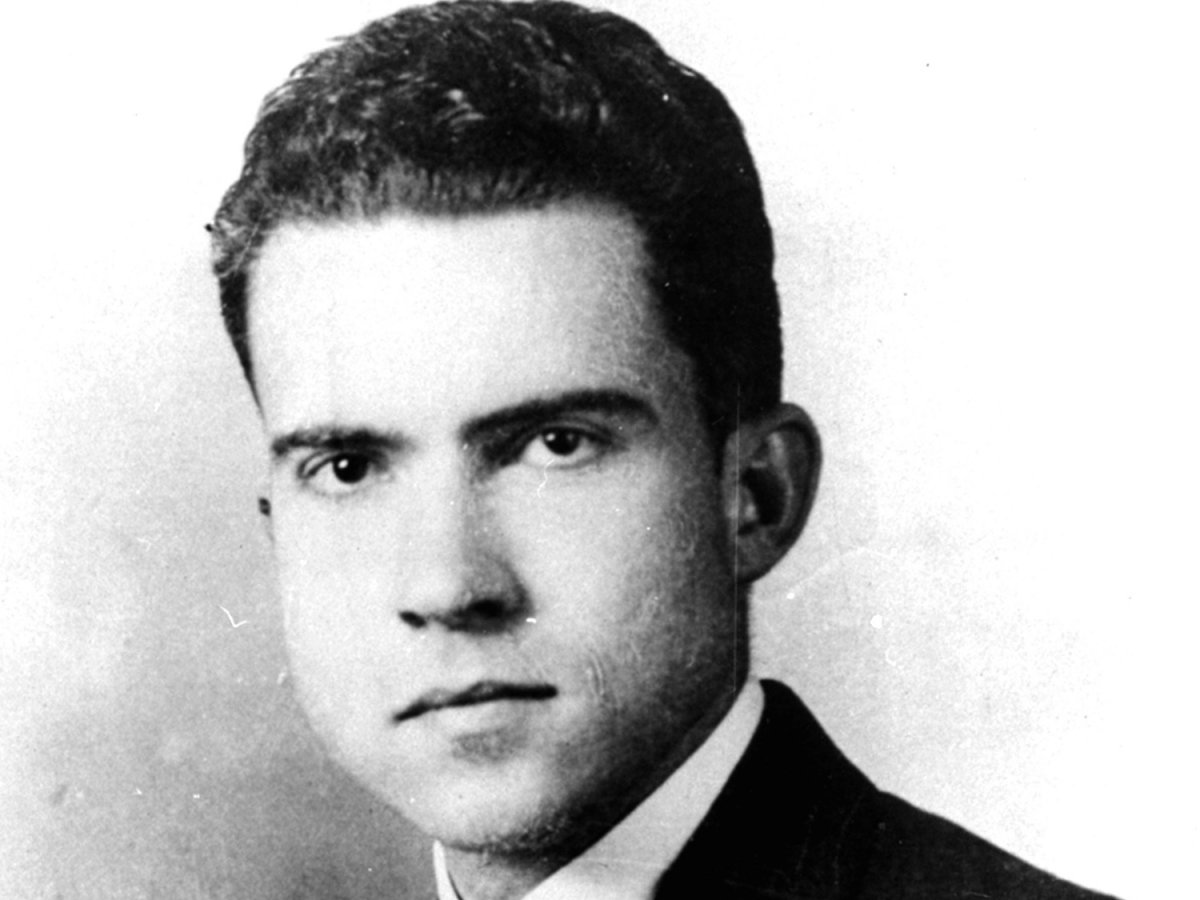

Richard Nixon, The Order of the Red Friars

Founded in 1913, The Order of the Red Friars was technically a semi-secret society at Duke University. New members were initiated, or "tapped" by a member of the Order donned in a red hood and robe. Sounds pretty mysterious, right? Well, apparently this all would happen on the steps of Duke Chapel in the middle of the day.

The society was apparently invested in improving life on campus. But among the red-robed ranks of the semi-secret Order was one law school student who would eventually juggle a few secrets of his own: Richard Milhous Nixon.

There's not much information about what Nixon got up to as a member of the Order, but Duke University's library lists him as a member. The Order voluntarily disbanded in 1971, only a year before the Watergate burglary set a series of events in motion that would unravel Nixon's presidency.

Gerald Ford, Freemasons

So far, Gerald Ford has been the last Masonic president (that we know about). He was raised to the order on May 18, 1949, in Columbia Lodge No. 3 in D.C. Later on, in 1975, Ford was made an honorary grand master of the Order of DeMolay.

That same year, Ford actually helped preside over the unveiling of the Masonic memorial honoring George Washington.

Ford's speech at the event, which was later published in his public papers, featured some reflections on his own Masonic journey.

"When I took my obligation as a master mason — incidentally, with my three younger brothers — I recalled the value my own father attached to that Order. But I had no idea that I would ever be added to the company of the Father of our country and 12 other members of the order who also served as Presidents of the United States. Masonic principles — internal, not external — and our order's vision of duty to country and acceptance of God as Supreme Being and guiding light have sustained me during my years of government service."

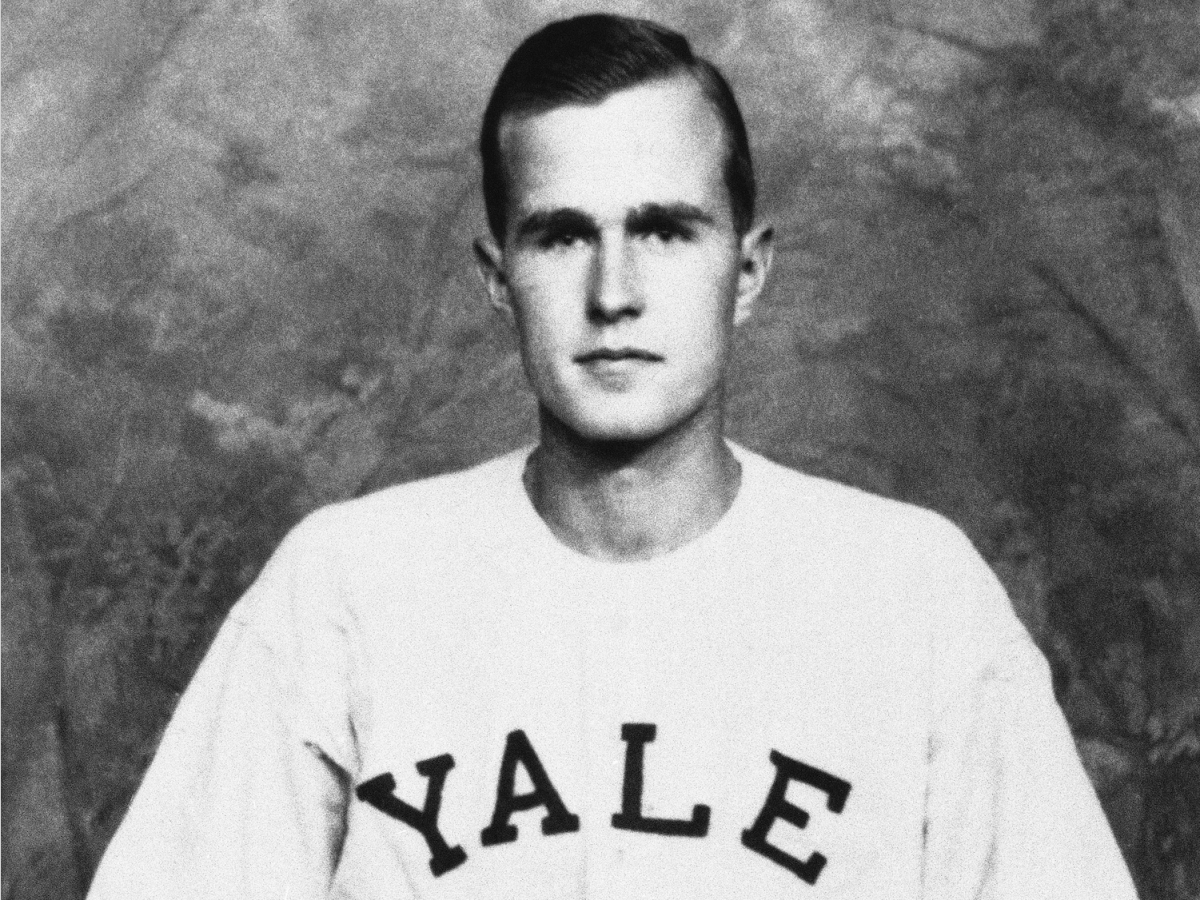

George H.W. Bush, Skull and Bones

Before George H.W. Bush became the second Bonesman to occupy the Oval Office, he was also a pilot in WWII and served as ambassador to Communist China, director of the CIA, and vice president to Ronald Reagan.

As president during the end of the Cold War, Bush supported space exploration. The American people have also criticized and exalted his involvement in the Gulf War, notably Operation Desert Storm.

George W. Bush, Skull and Bones

"W's" family name had become synonymous with Skull and Bones by the time he arrived on Yale's campus. There were rumors that Bush almost missed getting tapped by the group, but he ended up becoming the third Bonesman to become president.

We don't know much about Bush's time in the club. "My senior year I joined Skull and Bones, a secret society, so secret I can't say anything more," he wrote in his 1999 autobiography, "A Charge to Keep." Bush, however, carries a certain disdain for Yale's brand of East Coast elitism, as The Atlantic pointed out.

Christina Sterbenz contributed to a previous version of this story.